For nearly 35 years, Ana White has lived with the same unanswered question: what happened to her sister on the day she never came home?

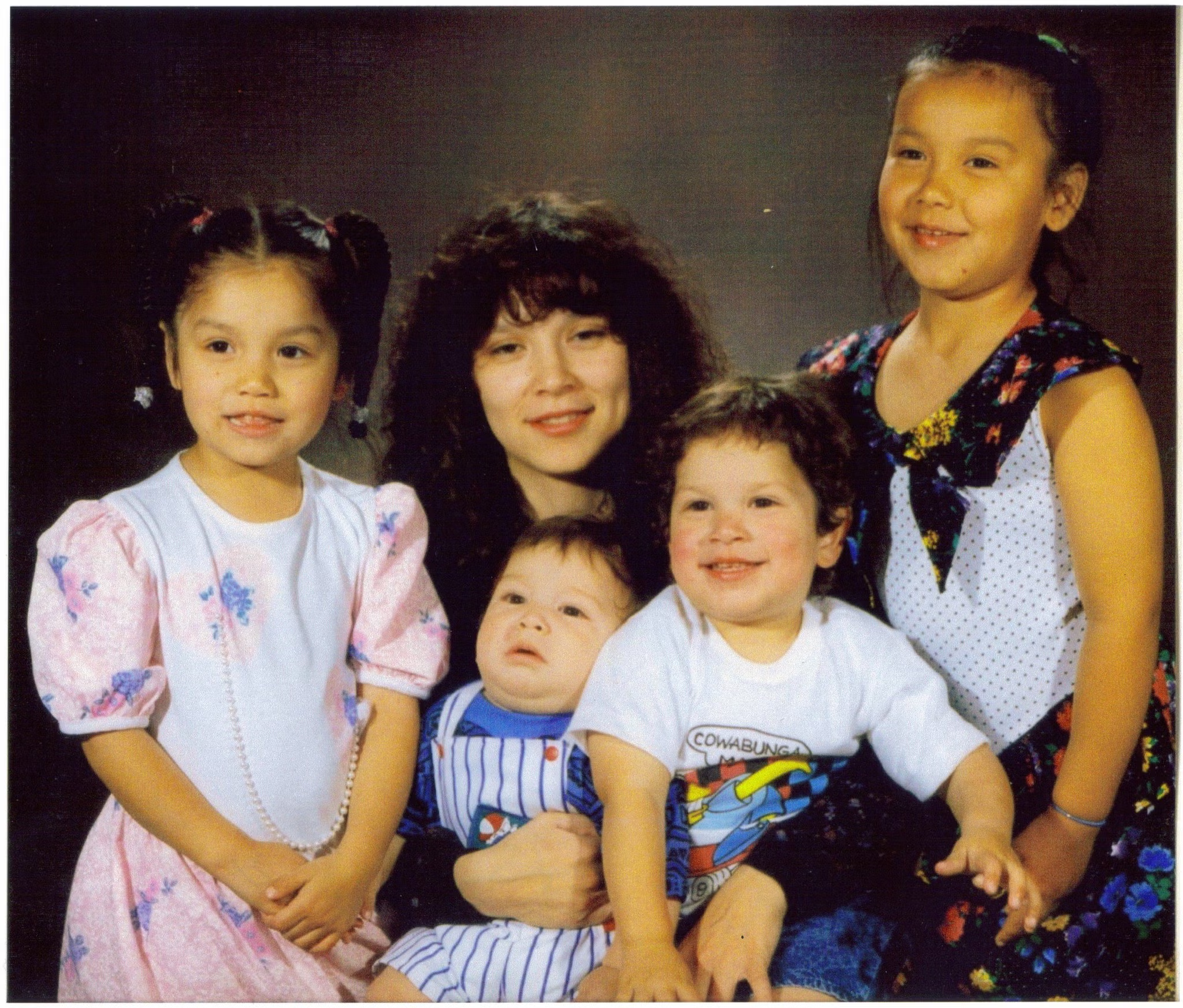

Andrea Jerri White, the youngest of the White siblings, was more than just a little sister to Ana. With a 13-year age gap between the two, Ana, the eldest, often cared for her as her own.

“She was like my baby – I’d get up in the middle of the night just to rock her back to sleep,” Ana recalled to The Independent. “She was just so special.”

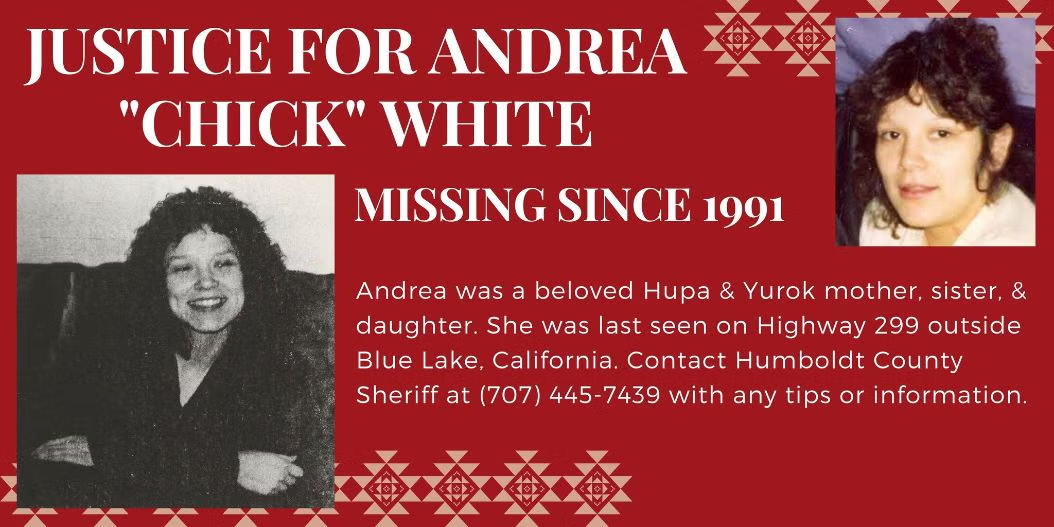

Known as “Chick” to her loved ones, White earned the endearing nickname at just nine months old, as she waddled around, resembling a baby chick, her sister said. The name stuck and she carried it on into adulthood.

The White family lived on the Hoopa Valley Reservation in northern California, a place Ana left at age 18 to escape her dysfunctional family and a growing drug epidemic in the community. She settled into a new life in Washington state, but stayed in touch with her sister, who remained in Hoopa and had a family of her own.

Then, when White mysteriously disappeared at the age of 22, everything changed.

“It’s like she just vanished into thin air,” Ana said tearfully. “And we still don’t know, 30 years later, where she is. I mean, how does this even happen?”

The years have passed without answers, without arrests, and without the kind of urgency her family believes the case always deserved. But now, a new reward could lead to the truth they’re looking for.

On December 30, the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office announced a $20,000 reward for information in White’s disappearance, renewing attention to a case that has long symbolized the dangers faced by Indigenous women – and the families left behind waiting for answers.

“Any little thing that might get us closer to finding a key that will unlock all this,” Ana said. “That’s what we’re hoping for.”

The reward includes $15,000 from the Hoopa Valley Tribe and $5,000 from the Bureau of Indian Affairs Missing and Murdered Unit. The sheriff’s office did not explain why the reward was announced now.

The sudden announcement has reopened old wounds, but also revived a fragile sense of hope for a family that never stopped looking.

Hitching a ride

Highway 299 cuts through the mountains of Humboldt County in long, quiet stretches — connecting the Hoopa Valley Reservation, where White lived, to Eureka, California, where she had been on the day she vanished.

White – half Hoopa, half Yurok – was last seen on July 31, 1991, after traveling back to Hoopa following a court hearing. The 22-year-old had been charged with a DUI after a car accident a few weeks earlier. Her four children, who had been in the car with her during the crash, had been placed with their grandmother temporarily.

But White, described as an amazing mother by her sister, had acknowledged her mistake and was doing everything in her power to get back to her children.

Investigators later confirmed that White did make it to the Humboldt County Courthouse in Eureka, according to local reports, though it remains unclear why she was late. She carried a borrowed duffel bag filled with clothes for court – a detail her family says underscored her determination.

Her son, Arnold Davis III, was only three years old when his mother disappeared.

“She was fighting to get us back,” he told National Geographic in a 2022 article that highlighted the crisis of missing Indigenous women in California. “That’s why she hitchhiked to court.”

Around 1:30 p.m. that day, an unnamed woman gave White a ride from Arcata and dropped her off near the Blue Lake exit on Highway 299 about 20 minutes, she later told police. The woman asked that her identity remain confidential.

Witnesses, including a Caltrans (California Department of Transportation) road crew and unidentified Hoopa residents, according to the police report, claimed that they saw a woman matching White’s description hitchhiking along Highway 299 towards Hoopa.

Some unconfirmed tips suggested she may have gotten into a 1964 Chevrolet Impala, according to local news reports, but that lead went nowhere.

White never made it home.

About a week passed before friends and family realized something was wrong after they had not seen White and were unable to get in touch with her.

On August 9, 1991, White’s aunt reported her missing to the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office.

“It’s like she just vanished into thin air,” Ana said.

A mother who never would have left

Ana said her sister’s disappearance was immediately alarming – and that it was entirely out of character for her to go days without contacting her children.

“She would never just … leave,” Ana said. “She lived for those children. Her whole life revolved around them. Everything she did, she did it for them.”

After surviving a tumultuous childhood, having lost their father to murder and a mother who left them briefly amid addiction, Ana said her sister was hoping to give her children a better life. And she did.

“She was the best mom,” Ana gushed. “And just this loving person who created a warm and safe home for her children.”

White married her high school sweetheart and they had two children. Their lives were shattered when he was tragically killed in a motorcycle accident. Once again, White was forced to pick up the pieces and keep going. She went on to have two more children with a later partner and stayed in Hoopa to raise her family.

On the day of the court hearing, Ana received a message from her sister, who was worried about not having anything suitable to wear to court – and about how she would get there at all.

Ana said she did what she could for her family, but expressed frustration with the many other relatives on the reservation who refused to step up.

“Why was no one there for her?” Ana said. “She was hitchhiking alone to court. With no support.”

But Ana does not doubt that her sister had planned to return to her family that day, and build a bright future with her children.

Investigators would later discover that White had gone to a furniture store that day to shop for a waterbed for her son, according to her sister.

To Ana, the purchase was devastating proof of intent.

“She was thinking ahead,” she said. “She was planning a future with her kids.”

The search – and a case gone cold

In the days after White was reported missing, law enforcement launched air and ground searches along Highway 299 between the towns of Blue Lake and Willow Creek, using ATVs, search teams, and a helicopter. Nothing was found.

More than a month later, authorities announced that they suspected foul play and continued to appeal for information from the public. The Hoopa Tribal Business Council offered a $1,000 reward – the first and only monetary incentive tied to the case, until now.

Over the years, theories about White’s disappearance have persisted.

White’s sister shared a deeply troubling allegation – that shortly before her disappearance, she had told their aunt that she had been sexually assaulted by a local law enforcement officer who had picked her up for intoxication.

A former Hoopa-area deputy was later convicted of molesting a 13-year-old girl, though that conviction was overturned and the case dropped when the victim declined another trial, according to Sovereign Bodies Institute reporting. That former deputy has not been named as a suspect in White’s disappearance.

For years, Ana has repeatedly prodded local law enforcement for updates on the investigation and continued to share her sister’s case on social media.

Then in 2021, a glimmer of hope emerged when Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a U.S. Cabinet secretary, announced the creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Missing and Murdered Unit, a new unit to investigate the epidemic of missing and murdered Native Americans.

The new effort gave Ana a renewed sense of hope that she may finally find out what happened to her sister.

“That’s what gave me hope that we’d find my sister,” Ana told The Independent. “Deb did that for us, for all of us. I knew she would be the key.”

Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office subsequently launched an online database of unsolved missing persons and suspected homicide cases and appointed two deputy sheriffs to a new cold case unit.

Andrea White’s case was on their list.

A case reopened – and a family still waiting

Last year, Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office reclassified White’s case as a homicide and reopened the investigation. Lieutenant Mike Fridley is leading the effort.

“We really want to see justice for Chick,” Fridley told the local paper. “We know there are people who may still be holding onto information.”

But progress has been slow, Ana said.

In November, White’s son Arnie Davis, who still lives in Hoopa and now has a family of his own, spoke out about his mother at a town meeting – hoping to bring awareness to her case and break through the silence.

“It’s been 34 years – 34 years of silence, silence from my family, from the Hoopa Tribe, and from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office,” he said, revealing that he knew very little about his mother except what was printed on her missing poster.

Davis and his siblings went to live with their grandmother after White’s disappearance.

“That’s as much as anybody cared to talk about it in my household,” Davis added. “Silence took over everything when it came to my mother.”

Davis said he had only recently been contacted by the sheriff’s department, now that his mother’s case is being reexamined – and that it was about a case file that was allegedly overlooked until now.

“That case file has been there since she went missing,” Davis said. “It took 34 years for somebody to get up off their a** and check storage and find a box… 34 years for somebody to finally do their job.”

White was 5 feet tall, weighed about 110–115 pounds, and had brown hair and brown eyes. She was last seen wearing Levi’s jeans, a white sleeveless shirt, a black leather jacket, and carrying a black duffel bag with white trim.

Anyone with information is urged to contact Fridley at 707-441-3024.

An epidemic of loss

The plight of missing and murdered Indigenous women is a crisis that has plagued the U.S. for decades, which advocates say is linked to myriad issues, including domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, trafficking, and systemic failures in law enforcement.

Thousands of Native American women are listed as missing, according to the National Crime Information Center, with 5,000 cases reported in 2022 alone. However, advocates believe that the true number is even higher due to underreporting and data gaps between tribal, state, and federal systems.

An NIJ-funded study shows that American Indian and Alaska Native women and men suffer violence at alarmingly high rates. American Indian and Alaska Native women experience a murder rate 10 times higher than the national average. More than four in five American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime.

And according to the National Institute of Justice, 56.1 percent have experienced sexual violence, 55.5 percent have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner, and 48.8 percent have experienced stalking.

What has hampered these cases, the Bureau of Indian Affairs says, is a lack of resources to investigate, whether that be questioning new witnesses, reexamining old evidence or keeping tabs on suspects.

‘That’s my mission’

For Ana White, who grew up protesting on the steps of the Eureka courthouse because of the injustice she claimed was rampant on the reservation, there was no other way but to fight. She’s hopeful the reward money will encourage someone to come forward.

But her fight began long before the reward – and it won’t end with it.

“I have nothing to do for the rest of my life but to find Chick – and that’s what I’m doing,” Ana said. “Doesn’t matter how long it takes me. That’s my mission. That’s what she deserves.”